Unfolding Communities

The lost Jews of UnslebenHistory

5th to 10th centuries CE

Im 5. bis 10..Jht. und im Hochmittelalter gründeten jüdische Siedler die Ashkenazi Judengemeinden in Mitteleuropa. Sie waren Migranten wie viele andere germanische Volksstämme der damaligen Zeit. Als sich später die Staaten bildeten, galten sie als Fremde ohne Bürgerrechte. Sie durften kein Land besitzen, keine Berufe ausüben, die durch die Zünfte geregelt waren. Es sollte dadurch jeder Wettbewerb mit dem traditionellen Gewebe unterbunden werden. Das heutige Unterfranken wurde damals vom Bischof auch als weltlichen Herrscher regiert.

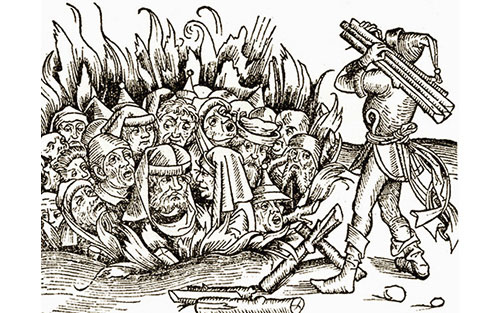

13th to 15th centuries CE

Beginning in the 13 th century pogroms occurred in larger cities like Würzburg, the capitalof Lower Franconia. As a consequence, the Duke decided in 1560 that all jews have to leave the country except for a certain class of more wealthy Jews, whom the Duke needed as money lenders and business men, mainly for export and import of goods. For Christian people at that time it was forbidden to take interest on lending of money and who would do it without? These upper class Jews got protection by the bishop, a monastery or other semi-independent institution.

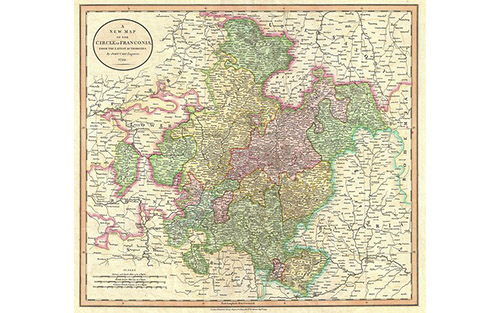

16th to 18th centuries CE

Leaving the country however did not mean that the Jews had to leave the outside boundaries of Lower Franconia, because it was a patchwork country with many very small islands of the estate of noblemen, who were not dependent on the bishop, but were directly linked to the Emperor. Such a noble man had his estate in Unsleben and therefor had the privilege granted by the Emperor to accept Jews under his protection. That of course was not without compensation and by the 18th Century the duties amassed from about 30 Jewish families amounted to about 25 % of the noble man´s budget.

Unsleben 1545-1810

In Unsleben, Jewish inhabitants are first mentioned 1545 in the context of a special contribution to finance the war against Turkish aggression. Here every individual family is listed with their assets and their contribution. Only the Jews are mentioned in bulk and their assets and contribution was equal to the poorest family in Unsleben. Therefor we can assume that at that time jewish population consisted of not more than one or two poor families. At a similar occasion 150 years later still only two families were listed. But from thereon a rapid increase occured. When the castle was sold from the Spessarth-family to another noble man´s family the „von Habermann“, already 26 Jewish families are listed under the protection of the owner of the castle. The number of families increased further. In 1810, 38 families were under the protection of the Habermann-family. At the same time about 140 Christian families lived in Unsleben.

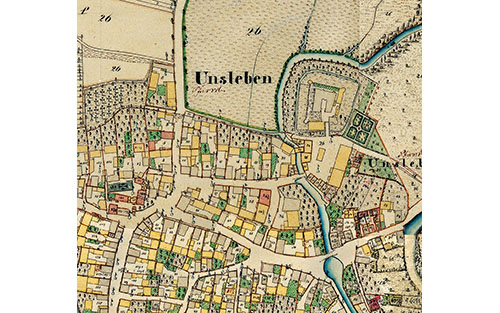

A Closed Town

Up till around 1830 Unsleben was a closed town. It had a crossroad with towers and doors on each entrance. Barns built against one another from tower to tower substituted a wall around the town. As a consequence, the number of houses inside the town was restricted. Only here and there a few small houses were built in the garden between two houses. Originally the Jews lived all within the farmyard of the castle. A few houses surrounding the castle originally owned by Christian vassals of the noble man. Step by step they were squeezed out and Jews rented or later also bought the houses. We know that up to five families lived in one house which nowadays is a one family house and number of children was higher than nowadays.

Housing Problems

This competition for houses therefore was in these early days a matter of irritation and annoyance between Christians and Jews. Jews not only had to pay their contributions to the noble man but also the catholic priest of the town claimed a New Year´s gift from them with the argument that while the Jews occupy former Christian houses consequently Christian young men wanting to create a family have to leave the town, because they cannot find a home here, which was a prerequisite for marriage and citizenship. A decreasing number of Christian families however were a loss for the priest, a loss of fees for services at baptism, weddings, and funerals.

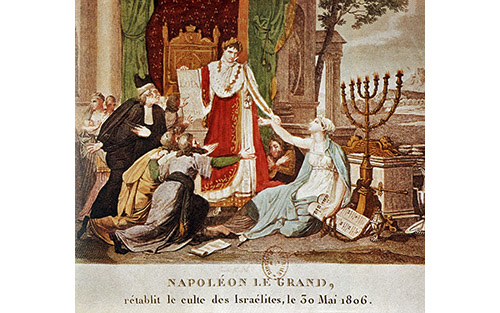

Liberty Equality Fraternity

The French revolution in the late 18th Century with its paroles „liberty-equality- fraternity“was the starting point of big changes also in the German states. Most important for our dukedom the bishop was deprived of his secular power and Lower Franconia became after a state of transition 1816 part of Bavaria. In Bavaria the so- called „Judenedikt“ in 1813 ( Regulations, which at the beginning of the 19th century were adopted by various German states to regulate the citizen- and canonical ratios of the respective Jewish residents.) brought certain rights for Jews. The independent status of the noble men was no longer acknowledged. As a consequence, the Jews had to accept permanent surnames. Up until then the name of the father had been added to the first name of the child (the firstborn male child got the grandfather´s first name).

Names

By 1817, the following names were taken by the Unsleben Jews: Lilienfeld Gottgetreu Donnerstag Kuhl Rosenberg Wollmann Lamm Dinkel Gärtner Mittel Kalb Langer Tuch Brandus Baum Lustig Thormann Liebenthal Hopfermann Bein Friedberg Engel Mutter Apfel Bach The underlined names were still known in Unsleben in 1932, in addition the follwing Jewish names existed in Unsleben in 1932: Blumenthal Brandis Goldschmidt Kälbermann Krämer Moritz Naumann Rose Rosenbaum Stern Strauß Wantuch.

Second Class Citizens

Through the Judenedikt the Jews became at least second class citizens, with more rights than before, but now they also had to contribute with taxes to the state. Only very few denied paying their original fees, but by around 1830 things had settled and the Jews were no longer double-taxed. In that process the Jews had to declare their assets as a base for taxation to the community and state. The mayor of Unsleben complained that the Jews were very slow in filing their tax base and furthermore that they seem to be very poor, but when they apply for citizenship and have to meet the minimum requirements for it they seem to be very rich. Up till 1816 the Jews evidently had been in general very poor. In 1833 the structure of the professions is listed as: 1 wholesale dealer, 14 craftsmen, 3 farmers, 24 peddlers.

Emigration

One of the restrictions still valid was that the number of Jewish families should not be increased, but there were exemptions. From population figures we can conclude that a lot of marriageable men and females must have been „parked“ within the families. This also led to the beginning of emigration abroad. One of the first ones was Simson Thormann, who settled in Cleveland/Ohio, at that time half the size of Unsleben. He worked as a trapper and fur trader; he left his girlfriend behind in Unsleben. Through his contacts with his home town he initiated the forming of a group of 20 people amongst them his girlfriend under the leadership of Moses Alsbacher that left in 1839, most of them settled in Cleveland and founded there a Jewish community.

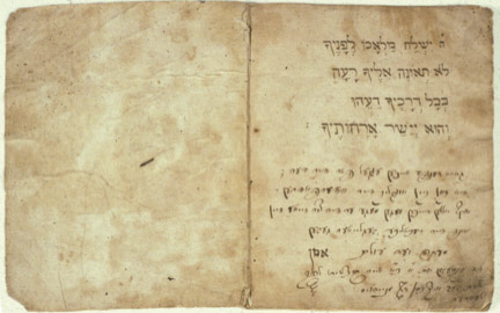

The Alsbacher document

As a farewell message the teacher Lazarus Kohn gave them a document with the names of all the Jewish families and their members and he impressively recommended to preserve their confession in the new world. It is an eloquent, prayerful message that asks God’s blessing on their journey and challenges them to keep their faith and resist the temptations of freedom. The booklet includes a prayer and ends with a list of 233 fellow Unslebeners – probably all the Jews in this town of about 1,000 inhabitants

The Synagogue and School

By 1837 the Jewish community felt strong enough to improve their situation by building a new synagogue and school. The old synagogue was a former farm building and was very shaky. Furtheremore, there was no extra school building. Thus, they bought from the state one of the grain barns, where farmers had in the past delivered their tax.They had in mind to use one story for the synagogue and the second story for the school. But in 1850, after 20 years of accumulating the funds, the architects they did not approve their intentions. So in 1853 a new school was built at a different place. In 1855 the original building was sold and the synagogue was built adjacent to the grain barn which afterwards became the granary of a Jewish firm Gebrüder Gärtner, later owned by the Naumann brothers until they had to sell it in the 1930’s. Costs of the new synagogue were 2500 guilders. The weekly wage of a worker at that time was 1 guilder.

Emancipation

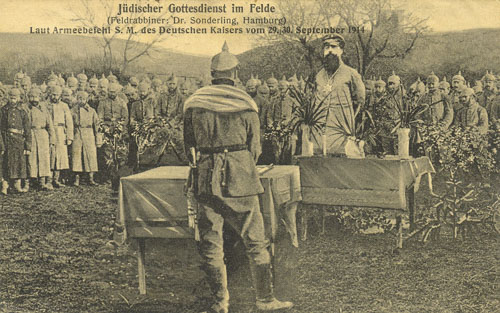

In 1856 a cemetery ground was bought on a hill one mile east of Unsleben. From 1856 until 1942, 229 funerals took place, 216 gravestones are still saved, 66 of them are anonymous, because the name plates were destroyed during Nazi time. The Jewish community grew further till the peak around 1860 with 60 families. From thereon emigration to the U.S. and to larger towns in Germany began. The former restrictions Jews had to face diminished. In 1871 emancipation of Jews was granted with the exception that they could not become lawyers or officers in the army. In 1906 the Jewish community counted 45 families, in 1935 just before the exodus began 35 families lived in Unsleben. In 1860 the Jewish school had 40 boys and girls, but by 1920 only 10 schoolchildren attended, maybe the same number was attending a higher school. In the mid-thirties 15 schoolchildren were instructed in Unsleben due to the elimination of Jewish children from public schools in nearby towns that were sent to Unsleben.

Integration

Through the hundred years from 1830 to 1930 Jews were completely integrated into social life of Unsleben, however they were not assimilated, because they kept their confession, their habits and holidays. Jews were accepted as neighbors, as citizens as business partners, as employers. This acceptance worked both ways. When Moses and Mathilde Gärtner, by far the wealthiest couple around the turn of the 19 th -20 th . Century, died in 1912 they had made a foundation; the interest of which was to be distributed equally among poor Jewish and Christian families of Unsleben. In the thirties to be of different confession, even to be a protestant in an otherwise 96 % catholic community was a slight stigma. So not all differences between Jews and Gentiles had been wiped out. Jews were accepted as members in the various clubs: Firemen, veterans, athletics, and even as members of the governing board. They had at least one member in the village council.

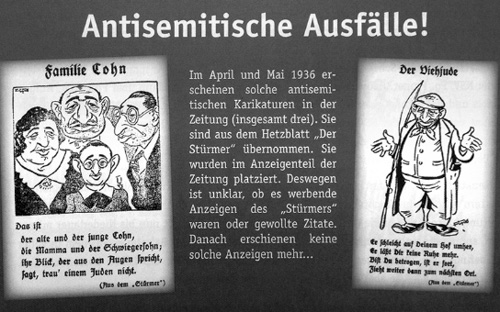

The Rise of Nazism

The peaceful and friendly living together was abruptly disturbed by enactments and commandments of the Nazi government, which came into power early in 1933. Any intercourse private or commercial between Jews and Aryans – non Jews – was forbidden. This decree was followed immediately in Unsleben. But from year to year people became more and more discreet, because there were of course also fanatic followers of the Nazi party among the inhabitants and it became normal to denounce neighbors, if they did not conform to the commandments. The consequence was the chance to end up in Dachau (the first concentration camp). This change in relationship with their neighbors and friends, business partners was hard to understand by Jews and was very violent to them. But on the other hand the system was so efficient in controlling their population and so radical in their penalties for nonconformity, that most people accommodated to the situation. The goal of the Nazi government was to get rid of all Jews in Germany.

Kristalnacht

Emigration between 1933 and 1938 however went slowly. Mostly single persons left. All this changed drastically in November 1938. The execution of a member of the German embassy in Paris by a Jew of Poland was the signal for an evidently earlier prepared nationwide action against Jews. Synagogues were set on fire; male Jews preferably richer Jews were arrested or even sent to a KZ. The goal was to force out Jews and get a hold of their property, since the government was planning and preparing for war and there was a need to finance it. In Unsleben the synagogue had already been emptied of the Jews in September. The Torah scrolls had been hidden in a neighboring barn. The synagogue was not set on fire, this would have been too dangerous for houses around it, but the interior was badly damaged and the benches were taken out. The catholic priest tried to rescue at least part of it and found a carpenter, who remade small stools out of the bench boards to be used in the Kindergarten. One of these samples was sentto the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland/Ohio.

The Demise of the Community

The male persons were hunted up by members of the Nazi organizations SA and SS in their homes, some of them had hidden and were found, some were not found. Twelve were chased to the central place in the eastern part of Unsleben and loaded on a truck and brought to jail in Bad Neustadt. After some days they were released again, but after that shock all of them hastened to prepare themselves and their families for emigration. Those who had an anchor where they could hook on could be lucky, because emigration could be arranged quickly. For others it was not easy to find a country to accept them. Some had to wait in Cuba for immigration into the US. In 1933 Jews made up 12,5 %, of Unsleben’s population. By the end of the war not a single Jew remained.

The End

Unsleben is divided by the main road running from Bad Neustadt to Mellrichstadt in a western and eastern part. Jews lived apart from a few houses along the main road only in the eastern part where also the synagogue and the school, also the castle as the former protection authority, was situated. The peaceful and friendly living together abruptly was disturbed by enactments and commandments of the Nazi government, which came into power early in 1933, to discriminate Jews. Any intercourse private or commercial between Jews and Aryans – non Jews – was forbidden. This decree was followed immediately in Unsleben. But from year to year people became more and more discreet, because there were of course also fanatic followers of the Nazi party amongst the inhabitants and it became normal to denounce neighbors, if they did not conform to the commandments. The consequence was the chance to end up in Dachau (the first concentration camp).

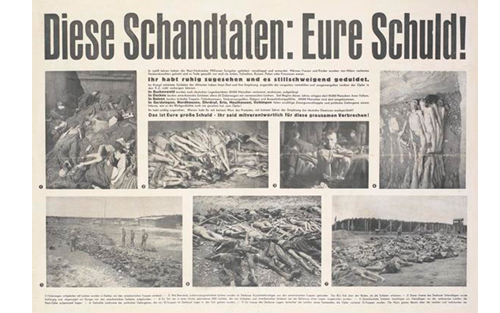

After the War

After the war a Jewish organization claimed the difference of the devaluated price of the property to what would have been a normal price. This was misunderstood by the new owners and they complained that they had to pay the property they bought twice a new issue of emotions against the Jews for most of the affected ones. It is true that people in Unsleben saw that Jews have been disgusted living there and emigrated and they saw the deportation of the last ones, but most of them were unsuspecting of what was awaiting them. Therefor after the war, when the truth became piece by piece evident, people became speechless and ashamed. And this state continued until the last ones that had consciously experienced this period have died out.

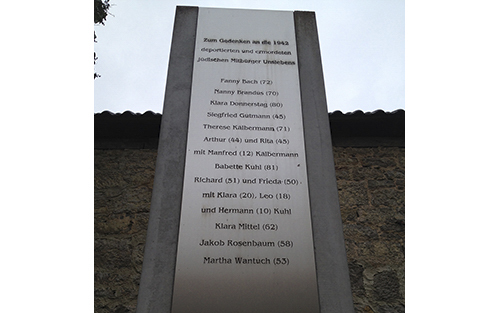

Remembrance

What remains as a permanent remembrance is that the meeting hall of the community once was the synagogue of a Jewish community and the existing of a cemetery, which serves as a demonstration object for children as early as in the kindergarten. To remember us on what once has been possible in our village and what never again may happen the community set up a monument honoring the victims of the Holocaust. After the war a few Jews visited Unsleben, went through the streets, looked at their former homes and visited the cemetery where their parents, grandparents, maybe even their partner was buried. Most of them did not contact the local people. In 1999 for the first time a group of about 40 persons, four of them born in Unsleben visited Unsleben and were heartily welcome by the community authorities and the population. Today the community is happy to welcome visitors, relatives of former Unslebener Jewish families and to show them the places where their ancestors lived and where many of them found their eternal rest.